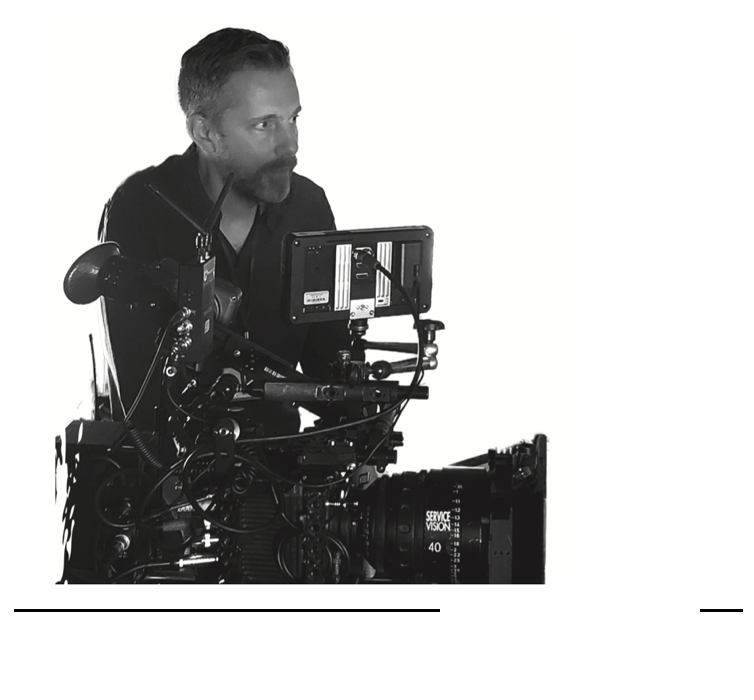

By: Roberto Bonelli

Freelance Movie Maker

In my time as a Production Designer for movies, I have had a great deal of challenges leading different crews to create the sets and dressing for movies big and small. However, in my eyes, the true leadership challenges I have had, have been the times when I was sent abroad to design commercials with different local crews. Commercials are produced very differently than movies. Not even on major commercials, such as spots for the Superbowl, does the Production Designer get to bring his favorite crew but will have to work with what is available locally. Most of the time very competent people, but because of the short timeline for these commercials, there is not enough time to really get to know one another before the project is deep in its crucial phase, and it might be too late. As a Production Designer, apart from being creative, it is essential to inspire and lead people to realize the projects, and the less time you have, the harder it is.

I know that the film industry is a very specialized world, but I also feel that basic management can be applied to other industries. Based on my experience, these are the five steps to follow to lead a group of people that you have never met and that you will only be leading for a short while.

- Break the ice.

- Adapt to the local way of doing things.

- Be clear.

- Lead by example.

- Don’t trust the translator.

Before we go into details, here is first is a little outline of how we make commercials:

Once the job is awarded, I get sent the director’s treatment and info on the country where we will shoot the commercial. That info is usually the available locations, budget, and available crew. Together with the director, we select the best locations we want to see once we get there. Then, I chose two key collaborators from a list of proposed Art Directors and Set Dressers. If I am really lucky, someone who if have worked with is available, but in general, I have to choose someone new. If I am unlucky, there may not be qualified options available. Before arriving in the chosen country and meeting my new crew, I might have had a kick-off call or a video meeting, but that’s it, and by the time we get to sit down together, there are two to three weeks until we start filming. Considering we need to design sets, have them approved by the director and the advertisement agency, and then build them, time is usually really against us.

So, my newly hired local Art Director and Set Dresser will already have their own assistants, but since we usually shoot in multiple locations, I do have a lot of direct contact with all of them. Often, a Set Dresser assistant will pick me up to scout the Prop Houses while the Set Dresser visits stores and the art director starts the construction of the sound stage.

So, how do I get all of these people to work optimate?

1. Break the ice

Share a personal side of yourself and not just the professional you. Open up a little. You don’t have to lower your professional guard, and you shouldn’t come across as fake or unserious but find a balance where you can be professional and open at the same time. Getting through in a sincere way can be vital for running a group with people you have just met. Don’t just share our success stories but share difficulties you have had on previous projects. Your key people should feel they can share problems with you instead of resolving them behind your back. You telling them to do so is not a guarantee that they will actually do it, but if the ice is broken, you stand a better chance of them trusting you. I usually tell them that I can help solve their problems. For instance, it sometimes happens that there are budget issues. The local crew will most likely prefer not to provide what you have asked for rather than going over budget since they have the financial responsibility and need to stay on good terms with the local production company. It is, therefore, essential that you are part of resolving those issues to get what you need.

2. Adapt as much as possible to the local way of doing things.

The structure of any Art Department can be set up in many ways. I believe that it is not a good idea to impose methods but to figure out together what fits the project best. Ask your local key crew to explain the planned setup. It is not a bad idea to explain how things are usually done in the U.S. and, indeed, in other parts of the world, but if they have objections, I recommend listening and adapting. Northern America and Europe usually have smaller but more specialized crews, while countries with smaller film industries will often just add more assistance to compensate for the lack of skills. In certain cases, it is better to sub-hire providers to take care of parts of the job because there is skilled labor in every country, but they are not always in the local film industry.

An example of this is a staircase. It can be built of wood, metal, concrete, or something else. So, if it turns out that there is a great local tradition for carpentry, then that is probably the best way to go. Of course, you should not let your assistants bully your vision or ideas, but maybe they can be adapted to a way your crew feels more comfortable with. If you do need to put your foot down and insist, do it. Be firm but fair and show them that you were open to suggestions but feel strongly that your way is the correct one in this case.

Its kind of goes without saying, but I will say anyway since part of my philosophy is not to take anything for granted: You have to follow the laws of where you are working. Labor laws are different. Most important, you have to adapt and respect the agreed working hours of the place you are in.

And don’t complain about petty problems. Not everything is like home, and we sometimes get spoiled by the excellent service we get in certain places. You are there for work and not on holiday. You need to keep your comments to important work-related issues. Then your comment will be more effective.

3. Be clear (and don’t use slang or abbreviations).

Make sure that your crew has understood their responsibilities and deadlines. Be crystal clear about what is expected from them and ask them if they feel they have the foundation to deliver. Let people know that you expect some misunderstandings to happen but that everyone should make an effort to be clear to keep them to a minimum. A small example is not using abbreviations or expressions that are not common worldwide. Nowadays, so much of our communication goes through text messages, which are often read at a glance while performing another task. Being clear and not leaving room for interpretation is very important. Take the time to write properly. Do not just forward e-mails but cut out the important information from the long chain you may have received and re-send only that part. I know this sounds banal, but you would be surprised how many producers and directors apply the forwarding of e-mails without further explication. Even though you understand it, you should not take the risk of your team members misunderstanding it. If you send your key people clear information, they will most likely pass it on in a clear way down the chain.

Also, let them know that there is no such thing as a stupid question. Your crew should feel confident enough to ask you questions, even ones they have already asked you. Film-making is very abstract and subjective, so the same question can have a new perspective once the process is a little more advanced.

4. Lead by example.

I find that it is essential that you are first in line when it comes to pulling the load. To make a commercial, the crew almost always works as long hours as is legally permitted. It is important that they see you do the same; otherwise, they will most likely opt for quicker solutions rather than better ones. Don’t arrive at the office hours after your crew. Even though you might be up late doing some kind of work, it is important that you are present and available during the hours your crew work.

Ideally buy the crew lunch (something fast but very good) and don’t disappear for long lunches while the crew is waiting for info or feedback to continue their work.

Make a big effort not to be late to meetings and let your team know in time if it is inevitable.

Let them know that you are always available if doubts occur. Waiting to make important decisions can affect your crew’s workload and, indeed, morale as well. Making hard decisions is your responsibility and the biggest reason that you are in charge. If you are indecisive and look nervous about it, you will have a hard time leading our crew. If you genuinely have a doubt about something, you could consider asking your key people what they think but just keep in mind that you are the person closest to the director and probably know better what is right for the project. It’s not about personal taste but was is right for the project. In fact, if I decline suggestions from my crew members, I say: ‘it is not right for this project.’ I then thank them for that suggestion and encourage them to keep suggesting.

5. Don’t trust the translator.

Another thing to be aware of is that things get lost in translation. If you are in a country where you don’t speak the language and have to use an interpreter, you should never trust that your message has gone through. The interpreter is usually specialized in language but not in the specific field that you are talking about. Therefore the communication should be as direct as possible. In the case of film design, we use plans or simple sketches. Paint and texture samples. I remember using an interpreter to communicate with a Chinese scenic artist who was painting a set. The painter was very good, and the translator spoke English very well, but the translator had never worked in an art department before. I didn’t have the time to educate the translator, so I tried to communicate as directly as possible with the painter, only using the translator for specific keywords. It was not without hickups, but it was surprising how well it worked.